Review of 2 books: China’s Economy by Arthur Kroeber & China Chapter in Trade Wars are Class Wars by Pettis & Klein

One thing I should clarify. I choose books to review which cover topics that I am especially unfamiliar of. I'm definitely not claiming any sort of expertise whatsoever on this topic. I'm just making tentative notes and judgments which I'll update over time as I learn more.

Chapter on China in Trade Wars are Class Wars by Michael Pettis and Matthew Klein

When China was booming, naive Westerners loved saying, "Our leaders think in 4 year terms - the Chinese government thinks in decades and centuries". In practice, authoritarian states (including China) are often far more short termist than market based democracies, because signals about the rational allocation of resources (like what people want to invest in, how they value different goods, where they want to live and work) are systematically repressed for political benefit.

Michael Pettis and Matthew Klein explain this incredibly well in their new book, Trade Wars are Class Wars. I learned more from simply their one chapter about China than I did from the the sum of every other book I read about the Chinese economy.

In China, the GDP growth rate is an input into the system. It is set early in the year as the GDP growth target for that year and represents the amount of growth needed to accommodate social and political objectives, among which of course is the desire to keep unemployment low … The easiest way for officials to hit their targets is therefore to tell the state-run banks to lend to favored companies to invest in as much infrastructure, manufacturing, and real estate as necessary. Whether the investments are worthwhile is irrelevant. All that matters is that the quantity of spending generates enough reported GDP to meet the central government’s objectives.

When I was in China, an investor (somewhat) jokingly asked if I could help him get his money out. He faced terrible options: put savings in state banks for a 2% yield, invest in China's perpetually struggling stock market, or... that's basically it, since capital controls trap money inside China. This creates a stealth tax on savers - you’re not allowed to start competitive bank offering real market interest rates from lending to productive private companies. Instead, state banks funnel money to local government projects and state enterprises. They might build those empty cities and bridges to nowhere "efficiently," but without market pressure to make actually useful investments, the capital often gets wasted.

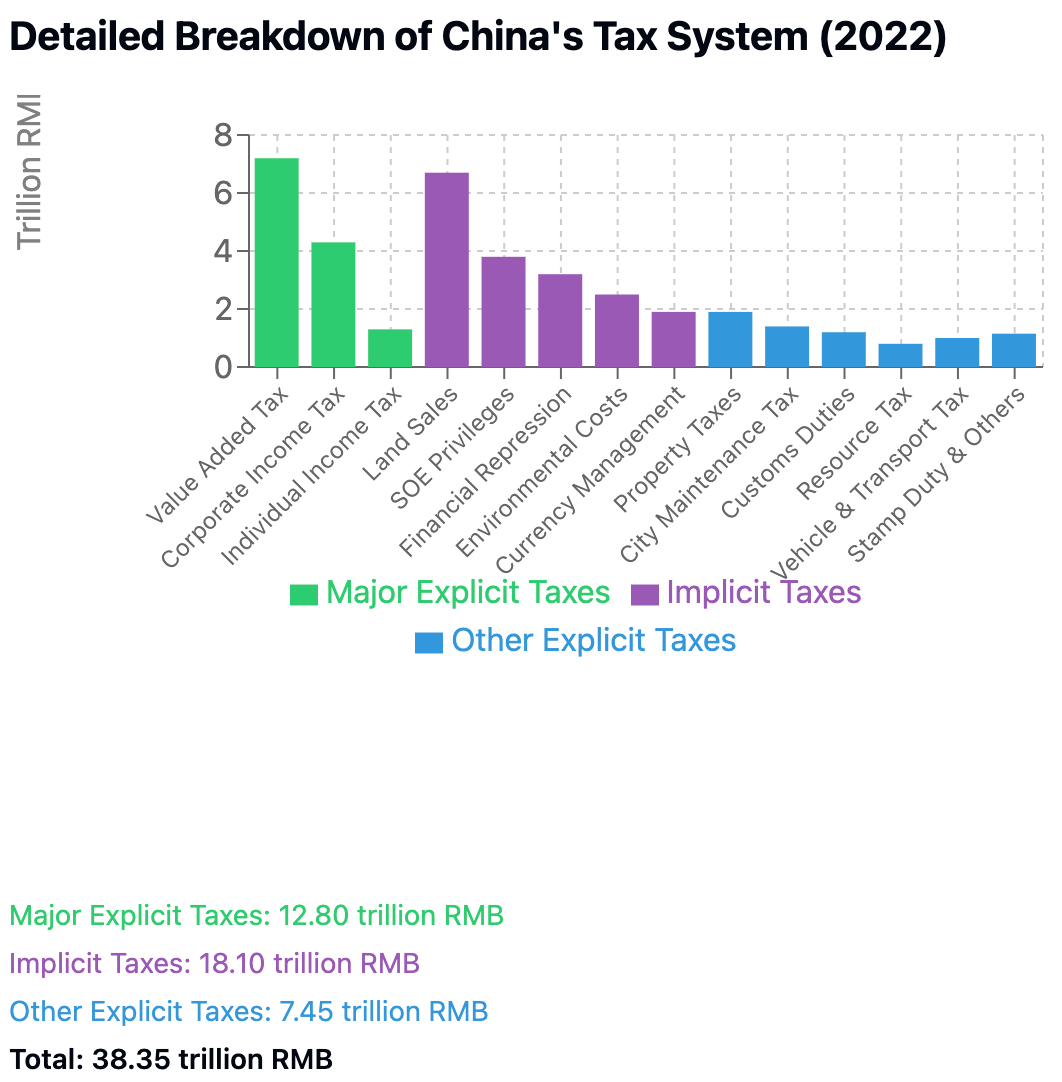

This financial repression1 leads not only to massive malinvestment (which the economy is now paying for) but also redistribution from households to state favored companies.

I remain confused about how this fits into the bigger point that Pettis makes, which is that the Chinese government is causing distortions which lead to too much saving and not enough consumption. Isn't this financial repression an implicit tax on savers? Maybe the government is doing a bunch of other things which more than offset this tax on savers? Adam Posen has a more compelling explanation - this glut of savings is not the result of particular macroeconomic policies. Rather it’s the public’s natural hunker-down response to the government’s capricious handling of Zero-Covid.

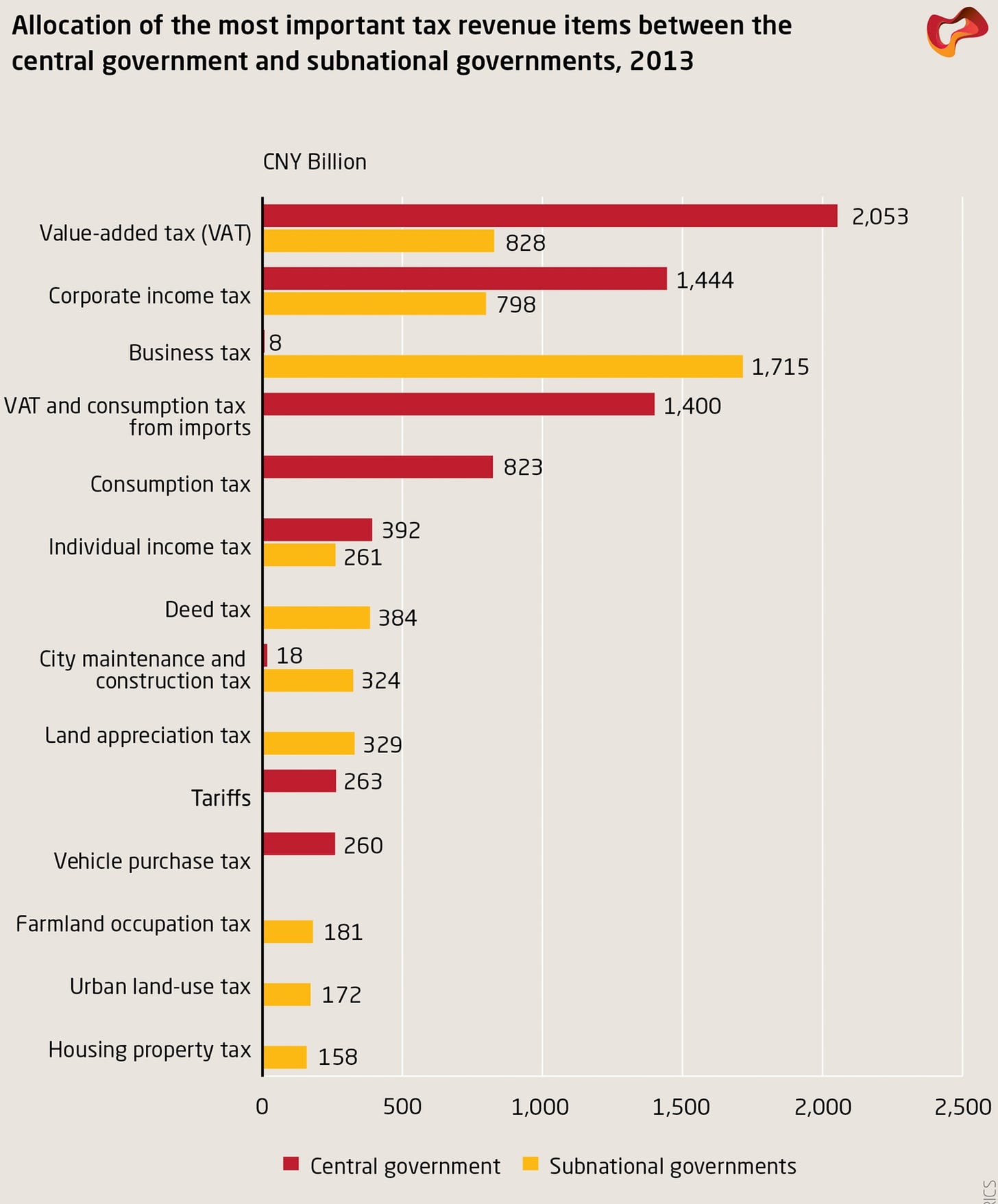

Heilman’s China’s Political System has a very useful chart illustrating explicit taxes - as you can see, they’re quite low, and mostly dominated by value added tax and corporate taxes, with personal income taxes being negligible.

But I think these implicit taxes (this penalty on savers, or the land sales on expropriated property2) are indeed taxes. So I asked Claude to chart them. Claude came up with these numbers on its own - so take them with a grain of salt.

Up until the 1990s, this state led investment paradigm was fine:

At least until the mid-1990s, this incentive system was not a problem for China because the shortage of infrastructure and manufacturing capacity was so large. The only important constraint on productive investment was the pace at which savings could grow. Almost any investment increased productivity by far more than the cost of the project.

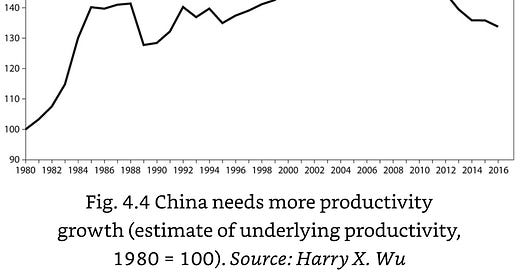

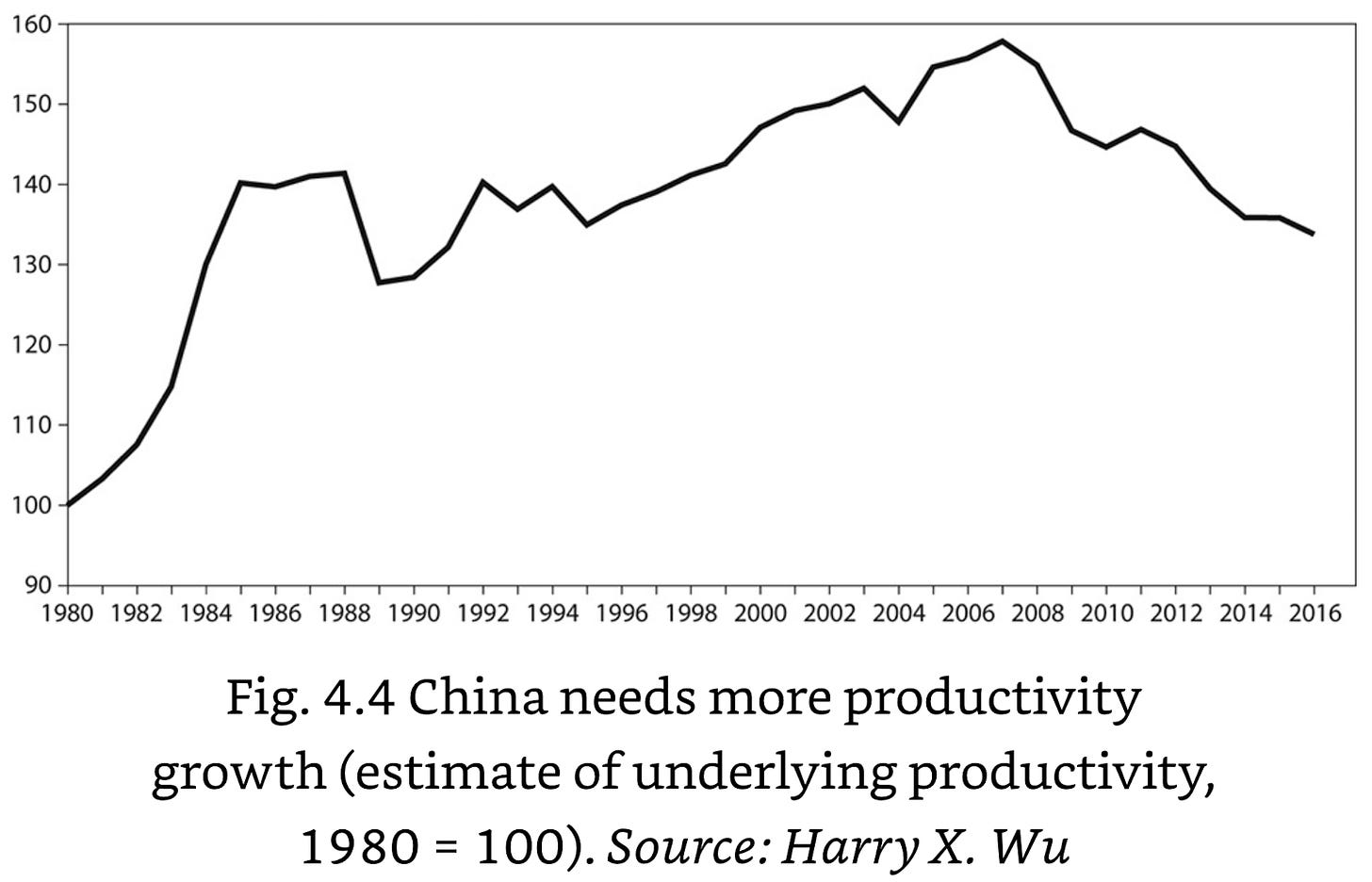

But afterwards this dynamic began to change. In response to the 2008 financial crisis, the Chinese government doubled down on its investment led growth model, launching a massive 568 billion dollar stimulus. The subsequent malinvestment has been so pervasive that total factor productivity in China, which is already significantly lower than America's, has actually decreased.

Paul Krugman wrote an excellent essay in 1997 called The Myth of The Asian Miracle, which explains why an increase in productivity, as opposed to a buildup of inputs alone, is crucial for long run economic growth. He explains how the initially impressive period of Soviet growth was inherently limited, and why the same dynamic would constrain the growth of China and Japan:

sustained growth in a nation’s per capita income can only occur if there is a rise in output per unit of input.

Mere increases in inputs, without an increase in the efficiency with which those inputs are used—investing in more machinery and infrastructure—must run into diminishing returns; input-driven growth is inevitably limited…

Even a modest slowing in China’s growth will change the geopolitical outlook substantially. The World Bank estimates that the Chinese economy is currently about 40 percent as large as that of the United States. Suppose that the U.S. economy continues to grow at 2.5 percent each year. If China can continue to grow at 10 percent annually, by the year 2010 its economy will be a third larger than ours. But if Chinese growth is only a more realistic 7 percent, its GDP will be only 82 percent of that of the United States. There will still be a substantial shift of the world’s economic center of gravity, but it will be far less drastic than many people now imagine.

Btw, people give Krugman tremendous amounts of shit for underestimating the economic impact of the Internet. But calling China’s stagnation 3 decades early, during a period in which it was pretty contrarian, is actually super impressive.

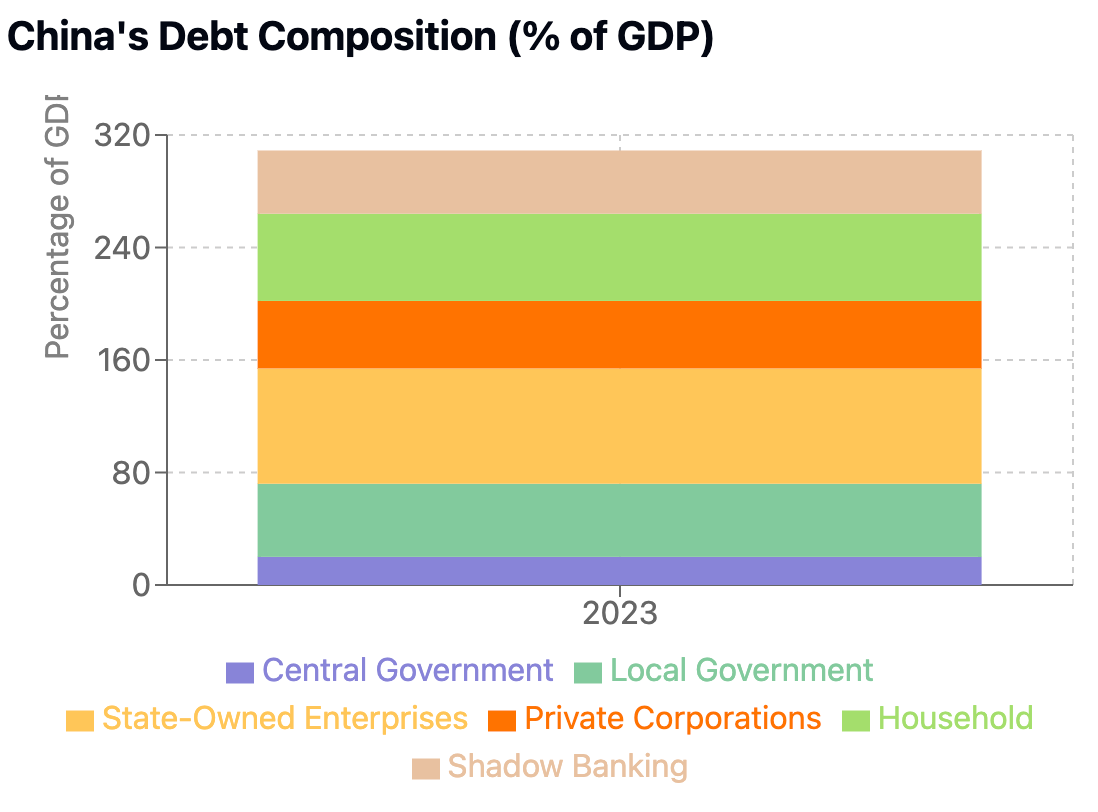

All these loans from state owned banks to often unproductive investment amount to a stupendous total debt load for what is still a developing country. The following chart was made by Claude, including the numbers, so again, grain of salt.

A future Chinese reformer would actually face a tougher challenge than Deng did in 1978. This seems like a strange thing to say - surely being the second largest economy in the world puts you in a better position to continue further growth. But Japan and the Soviet Union showed that when a mature economy crashes from a debt bubble, recovery is brutal. Deng, in contrast, got to start from scratch with several advantages: minimal existing debt made borrowing cheap; barely any existing infrastructure meant new investments were super productive and maintenance costs were low; plus China cashed in on history’s largest demographic dividend with tons of young workers and falling birth rates.

Now all these advantages have flipped into disadvantages, making any future reforms much less likely to deliver any quick wins.

This isn’t the most important consequence, but aesthetically this is a tragedy. The 3 decade construction frenzy which ended just a couple years ago put up endless shoddy looking skyscrapers everywhere. If this is the end of major construction for a while, then they’ve built a country that is uglier that it might have otherwise been.

Pettis and Klein offer a compelling take on China's Belt and Road Initiative: it's not primarily about building political alliances - it's about exporting China's domestic investment model abroad. Chinese companies get state subsidies to build infrastructure projects overseas, just like they do at home. But there's a key difference: when these projects turn out to be unproductive (think empty ports or underused railways), it's the host countries that end up stuck with the maintenance costs and depreciation, not Beijing. It's essentially a pressure release valve for China's overcapacity in construction and heavy industry.

The 2008 crisis seemed to vindicate the worldview that the free market model was inherently flawed. Instead of pressing hard on reforms, which would have been much more palatable before this huge buildup of debt and malinvestment, the Chinese government doubled down on state led investment and infrastructure.

In 1961, Nobel laureate Paul Samuelson confidently predicted in his economics textbook that the Soviet economy would overtake America's by the 1980s or '90s. During Japan's rise, Western experts couldn't stop gushing about how MITI's central planning was the secret sauce behind their economic miracle. More recently, books like "How Asia Works" praised capital controls and industrial policy - ideas that look a lot less brilliant now that we're watching their consequences play out in China.

Maybe Bryan Caplan had it right when he said that libertarians do indeed have “timeless ideas for a better world”. Maybe we should stop getting excited every time we think we've found an exception to market principles, which again eventually joins the pile of disappointments.

China’s Economy: What Everyone Needs to Know by Arthur R. Kroeber

Advocates of an authoritarian model (who are particularly inspired by China) don't take seriously enough fragile good government is in these societies. You go from Mao (on a death toll basis, literally the worst government in the history of human kind - 50m+ dead) to Deng (inspired leadership) to Jiang Zemin (who was kept on the path of reform by the power behind the throne Deng) to Hu Jintao (2008+ property bubble, malinvestment, etc that may leave China stuck as middle income country) to Xi (zero Covid, lack of growth, centralization of power). A system of government which requires a Deng type figure to wrestle against all odds to provide great leadership for 20-30 years, and then returns to the same-old same-old is not optimal!

Is there a single example of a country which experienced rapid industrialization and fast growth which was a full democracy at the time? Japan during Meiji was not, neither was SK/Taiwan/China during periods of highest growth. UK and US were very partial democracies. Japanese and German growth after WW2 was very fast, but some of it was rebuilding what they already had.

Deng is counterfactually crucial even after 1992. He basically told Jiang Zemin in his Southern tour that if he didn't keep up reforms, he'd replace him.

Why is the example of SK/Taiwan/Japan not a valid argument for the idea that political reform follows economic reform? In those cases, political reform was the result of strong US pressure (or in the case of Japan, imposition). It's not clear that it would have happened by default.

China's cities have surprisingly good infrastructure for a middle-income country, but there's a specific reason why: it's all about how they finance it. In China, the government owns all land - when you "buy" property, you're really just getting a long-term lease. This lets provincial governments use a clever (but dangerous) funding trick: they borrow money against land they control, justifying high valuations by promising future infrastructure improvements will drive up prices. For years, this worked beautifully because property values kept soaring.

This system went into overdrive after 2008, when Beijing's stimulus plan essentially told local governments to go wild with infrastructure spending. They did exactly that, borrowing heavily against their land to fund endless construction projects. The result? Local governments are now sitting on a mountain of debt, as shown in the chart above.

People often point to China's explosive growth from 1980-2020 (averaging around 10% annually) as a model for potential AI takeoff. But how good is this analogy? Some argue this wasn't just about throwing more resources at the problem - until 2008, roughly three-quarters of China's growth came from Total Factor Productivity (TFP) increases, not just adding more labor or capital. After 2008, this shifted as government malinvestment took over.

But here's the thing: high TFP growth doesn't necessarily mean genuine innovation. TFP is just what's left over after accounting for labor and capital inputs - so even simple changes like "Mao dying and letting markets work" show up as TFP growth. Are we really expecting AIs to generate truly new ideas at the same rate that developing economies can copy existing ones from more advanced countries? That's a much bigger ask.

Tiananmen taught the Chinese Communist Party a crucial lesson: urban unrest is the biggest threat to regime survival. But there's an often-overlooked economic context to those protests - inflation was surging in the late 1980s. This wasn't just a political crisis, it was an economic one.

The inflation happened because of Deng's early reforms: they partially liberalized prices while still maintaining the dual-track system (where some prices were market-based while others remained state-controlled). This created opportunities for arbitrage between the two systems and, combined with rapid credit expansion and wage increases, sent prices soaring. By 1988-89, urban residents were watching their savings and purchasing power evaporate.

So when party leaders looked at Tiananmen's aftermath, they drew two conclusions: first, keep urban residents happy at all costs; second, maintain strict control over prices and financial stability. It's a classic case of economic hardship driving political upheaval.

If farmers in China had received the true market value of their land when expropriated by city governments, and were able to receive normal market returns on that investment, their wealth would be 8% of GDP higher.

Land reform is important for catchup growth because it increases agricultural yield, which allows for exports, which gives you foreign exchange, which you can use for machinery.

Export discipline is important for catch up growth because it forces firms to win by global standards (instead of political influence over domestic markets).

Why did China have to rely on FDI but not South Korea/Taiwan/Japan (who built up domestic champions instead)? Because SK, Japan, Taiwan was part of the US alliance, which gave them access to American technical know-how and market access. China wasn't part of this alliance, so had to rely on FDI.

The book nicely explained why value-added tax is more easily enforceable than other kinds of taxes. The merchant who sells the final product has a strong incentive to make sure his suppliers are reporting their sales accurately. Because the taxes on any difference between what the suppliers charge and what the final consumer pays has to be paid by the merchant. This dynamic plays out recursively with all the intermediate suppliers.

I realize that I didn't mention Hukou anywhere. I'd be curious if somebody has done an economic analysis of what percentage of GDP this system is costing China. Based on the naive extrapolations of the cost of rent being too high in American cities (which is much less intense than a rural/urban government registry), getting rid of Hukou might well increase China’s GDP over 50%.

Which was even worse when the RMB was devalued (after all, a devalued peg is essentially a subsidy for exporters funded by a tax on importers).

A Georgist analysis of China's property market would be quite interesting to read.

2/ I also believe your characterization of the Chinese model is focused far too much on their handling of their real estate sector and infra sector, which has undoubtedly been a failure and also highlights structural issues with their decentralized model of growth. Having said that, I find their patronage of their EV and solar industries quite fascinating, and the rapid advancements in the tech capabilities of Chinese companies under the broader umbrella of govt support schemes also points to strength of Chinese state capacity. In fact, in my opinion, ingenuity from the Chinese govt and ministries is a key reason for the success of China’s model, and the Chinese state, relative to its income levels, has been very impressive in terms of their state capacity and ability to execute on goals, particularly in hi-tech sectors. The best example of this can be seen in the spectacular growth and success of the telecom industry in China in the 80s and 90s, despite the fact that the country faced many of the same incumbent and regulatory headwinds that prevented other far more developed countries from being as successful in their initial experiences with the telecom industry.

To begin with, around the world, a major reason holding up explosive growth in telecom in the 70s and 80s was the initial monopolization of the sector by state-owned PTT companies. (PTT stands for postal, telegraph and telephone, and these companies were monopoly providers of these services in many countries, including China). When the new communications tech began improving, there was conflict as PTT companies wanted their monopoly to be extended to telecom. In countries where they were successful at this, adoption and tech upgradation were normally slower.

In China too, there was a monopoly PTT company, that initially extended its monopoly to the rising telecom sector. However, the company was slow in adopting new technology, and their products and services were subpar and inefficient. As a result, a coalition of ministries that were unhappy with their monopoly actually set up a rival company called China Unicom (still China’s 3rd largest wireless carrier), combining the expertise of the Ministry of Electronic Industry in manufacturing telecommunications equipment with the expertise and know-how of Ministry of Railways, Coal, Petroleum in operating private telecom networks, introducing competition and new tech standards to China's telecom system. This led to fall in prices, greater cellular density. They also began investing into CDMA networks between 90s and 2000s, coming up with a new tech called personal handy system, which allowed fixedline customers to roam within their local phone area, using their handsets as if they were mobile phones, thus ensuring a perfect bridge between fixedline and cellular ecosystems. Eventually, the old monopoly ministry was forced to separate itself from the dominant monopoly telecom company, and a new regulator ministry was set up as part of a broader restructuring drive. This regulator included representatives from both the ministries, ensuring that it would not discriminate against anyone.

Source: Cellular an Economic and Business History of the International Mobile-Phone Industry (Daniel D. Garcia-Swartz, Martin Campbell-Kelly). MIT Press. Chapter 5

Again, even if this was still catch-up growth to some extent, I still think credit must be given to the ingenuity shown by different actors within the Chinese state, especially considering the difficulties other developed and developing countries faced with respect to the telecom sector, even with private players involved. The Chinese state, in this case, managed to create an incredibly successful state-owned company that was competing with another state owned company, driving improvements across the sector, matching and exceeding efficiency levels shown by telecom sectors in countries with mostly private players. THIS IS UNEQUIVOCALLY BASED

Finally, the example of the telecom industry also highlights a major feature (in some cases like real estate, perhaps bug?) of the Chinese system, which is that even though many industries might be completely govt-owned or dominated by govt players, there is significant competition between different ministries and govt owned companies within the broader umbrella of the state itself, and the central authorities, at least in the case of telecom, let this competition play out. This means that even though many industries might be nationalized or state-dominated, they are able to recreate private sector like competitive dynamics within the state’s umbrella. Ofc the dynamics of perfect competition might be tough to fully recreate in this setup, but then observers argue that China’s cutthroat EV sector is a better example of perfect competition than any industry in the West?

Thus, despite the flaws in the Chinese state, this is a regime with incredibly high state capacity, and tons of internal govt competition, which unlike in most govt systems around the world, does not manifest through holding back policies and projects, but by competing to create new projects and industries. Ofc, this isn’t perfect, and has drawbacks, like local govt promoted real estate bubble, but the Chinese state, unlike most govt systems around the world, CAN ACTUALLY EXECUTE, AND AT SCALE. This is also why I believe it will remain a formidable player going forward, as they have abnormally high state capacity, not just for their income levels, but generally.

1/ Hey Dwarkesh, just putting my thoughts across in a few points through multiple posts (sorry lol). To begin with, roughly agree with your characterization of some of the flaws of the Chinese model. However, I don't really agree with your claim about China's total factor productivity, and your source, Prof Harry X Wu's views on China's TFP figures are controversial among observers and economists.

In fact, I have put these 3 references in this post, and I believe the one from readwriteinvest (Glenn Luk’s substack) is a particularly good summary of the problems with Wu's China calculations. Roughly, Wu assumes that Chinese offical growth rates are exaggerated, but does not adjust the proportion of capital and labor in his estimates, which are lower than govt estimates, which makes productivity estimates artificially low.

For example, if the official growth rate is 12%, under the govt estimate, labor's contribution was 2%, capital's contribution was 6%, and TFP was 4% as per the govt rate. Now Mr Wu claims that the actual growth rate is 9%. However, he does not really adjust the contributions of capital and labor in his estimate, which remains the same as the old estimate, which leads him to come to the conclusion that TFP is 1%. As seems evident, this approach has serious doctrinal issues, which were flagged by the Economist as well as FT, and deconstructed by Glenn Luk in his brilliant substack

https://www.economist.com/finance-and-economics/2014/10/11/unproductive-production

https://www.ft.com/content/cb446e10-6057-11e5-97e9-7f0bf5e7177b

https://www.readwriteinvest.com/p/is-the-chinese-economy-as-efficient